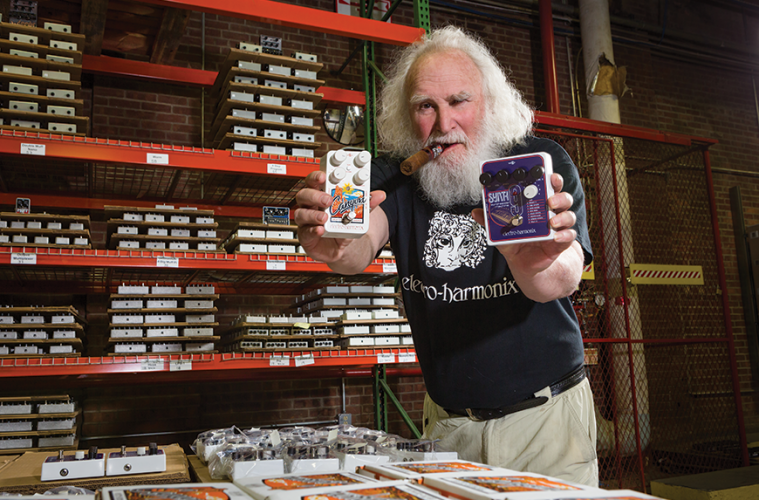

One thing that separates the music industry apart is the great stories we often get to hear. The Music & Sound Retailer presents one of MI’s greatest storytellers, Electro-Harmonix’s Mike Matthews. This month, we can all enjoy a great Jimi Hendrix story. But Matthews doesn’t stop there, providing plenty of information about his company. Enjoy.

The Music & Sound Retailer: Please tell us about your career and how, why and when you founded Electro-Harmonix.

Mike Matthews: Ever since I was five years old, I was into business. I always knew I wanted to start my own business. I grew up in The Bronx (N.Y.) in the 1940s. I used to fish balls out of the sewers with hangers, and sold them. I moved on to lots of different entrepreneurial things, including shining shoes. I bought a person’s inventory that was making binoculars during World War II. I bought all of his prisms and lenses. I sold them in junior high school, creating a big fad with prisms. There were rainbows all over the schools. Teachers didn’t know where they were coming from. When I went to camp and kids were playing golf, I would be in the pond looking for golf balls to sell.

As far as music is concerned, when I was very young, my mother gave me piano lessons. I was five. I had a formal, classical teacher a year later. When I was six or seven, I took part in concerts at the elementary school. In the fourth grade, I was rambunctious. I was scheduled to give a concert and I climbed up the rafters in the classroom. To punish me, the teacher canceled my concert. So, I quit playing. But in high school, when rock and roll was first evolving, I started getting involved in boogie-woogie on the piano and I got pretty good at it. At college at Cornell [University], I formed an R&B rock and roll band. That’s where I got into really playing music. I was booking all the gigs for our band. We didn’t just play at Cornell, but at Dartmouth, Lehigh, Hamilton, Colgate and Syracuse. Those were great gigs. They were mostly at fraternity parties. In those days, all the songs were cover songs. We played songs and people could dig it after just one bar. The legal drinking age was 18 and people would get drunk, but when they did, fraternity brothers would step in, so there weren’t really any fights that lasted more than a few seconds. Those were the best gigs.

While in college, I would promote rock and roll bands. I handled The Coasters, The Isley Brothers, The Drifters, The Rascals, The Byrds, The Lovin’ Spoonful and dozens more. I even became good friends with Jimmy James, who eventually went back to using the name Jimi Hendrix. I was promoting Chuck Berry at the time and I played keyboards and got some dudes I knew that did mostly Chuck Berry songs to back him up. The guitar player, Steve Knapp, for the backup band I got for Chuck Berry, said to me, “Hey, you’ve got to see this guy playing.” That was Jimmy James. I became good friends with him. I used to hang out with him at his hotel room. He was living in a fleabag hotel in Times Square with no bathroom. There was just a bed and nothing else. We would just have band talks about this player, that player. Later on, when Jimi Hendrix came back to New York City to record, he’d always invite me down to his sessions to hang out. I liked the way Jimi recorded. Most bands had everything rehearsed to the T. Jimi would just jam, and when he felt the groove was right, he would signal the recording engineer to record his stuff. His music would have a fluid, natural feeling as opposed to an over-rehearsed perfection that would lose some groove.

I knew I would always go into business, but before college, my father told me I needed to pick a major. I just selected electrical engineering. I didn’t desire to be an electrical engineer at the time. My first job out of college was at IBM in 1965. I went there because the job was in New York City and I figured it was the best environment to figure out what business I wanted to go into. While I was at IBM, I had an urge to quit and go out and play with a band full time. In those days, “Satisfaction” was the longest-running No. 1 hit of all time. All of the music stores in New York City were on 48th Street. There was a repair guy there named Bill Berko who was making fuzz tones, something everyone wanted then, one at a time. He said, “Hey Mike, why don’t you come in with me? We can make these much faster.” I said, “OK.” I figured I’d make some money with him and maybe I’d make enough so I could quit IBM. But it turns out he didn’t do any work, and I ended up doing that myself with a contractor in Long Island City. The founder of Guild Guitars [Alfred Dronge] wanted to buy all of them. So, every week, I’d bring a few hundred products out to Guild Guitars in Hoboken, N.J. They would write me out a check, and I would go back to work. Jimi Hendrix was hot at the time, and everyone wanted to sound like him.

I hooked up with Bob Myer, an award-winning designer at Bell Labs. He has about a hundred patents. He even invented something that’s the foundation for the cellular telephone. I contracted with him to design a distortion-free sustainer. In those days, there was no problem having sustain. The problem was if, all of a sudden, you hit a new note, the gain would be so high there would be all these pops and clicks. I’m not a guitar player, but I went out and plucked single notes to test one of the prototypes, and I saw in front of the big box for the initial prototype for the sustainer was a little box. I said, “Bob, what is the little box for?” He said he didn’t realize the guitar signal was that low, so he just built a little preamplifier to boost the signal. That preamplifier only had one transistor. I tried that and all of a sudden, the amplifier was so loud. In those days, amplifiers were designed with a lot of headroom. There was no such thing as overdrive. So, you would turn them up to 10 and they would still be clean and loud. But with this device, you could make the amp much louder, but then overdrive it. I made that my first product. I called it the Linear Power Booster, or the LPB-1, in 1968. I started selling those mail order and then in stores. We still sell tons of LPB-1s today. In 1969, I developed the Big Muff. We still sell thousands of those today, 47 years later.

The Retailer: The Jimi Hendrix story is fascinating. Can you tell us more about him?

Matthews: Jimi was a just a nice guy, and we used to hang out. I can tell you one story. The last time I saw Jimi with this band Curtis Knight and the Squires, I sat down with Jimi, and he said he wanted to quit the band. It was just a hobby for him. Jimi said, “I want to be the front man for my own band.” I said, “If you want to be the front man, you have to also sing.” He said, “That’s the problem. I can’t sing.” I said to him, “Look at Bob Dylan. Look at Mick Jagger. They can’t sing. But they phrase great and people love them. They are superstars. You have a great soul, and it will come out in your phrasing.” He said, “I’ll try that.” I think that chat helped him when he went to England and invented this whole new style.

The Retailer: What are your day-to-day responsibilities today? Take us through a typical day.

Matthews: I try to keep my hands in everything. I founded the company in 1968 with a thousand dollars. I tried to double our sales every year. I was always pushing the company for more and more sales. Whenever we had a problem, I would solve it. Finally, in the early ’80s, I had too many problems all at once and I collapsed and went bankrupt. I went on to do other things. I got involved with Russia because we exhibited at a trade show there in 1979. I got involved with vacuum tubes. But I noticed in the early ’90s that all the products I had made in the past were selling for much more money. This new, vintage market developed. So, I figured I would start to make some of those products again. The Russian economy collapsed at the time with the collapse of the Soviet Union. Almost every factory in Russia was a military factory. They collapsed and were looking for work to survive. So, I hooked up with a small military factory in St. Petersburg that made testing equipment for the army. I just gave them the circuit diagram of the Big Muff. They redid the circuit board, redid a chassis and more. The sound of the Russian Big Muff was slightly different than the original Big Muff. In 1993, we reissued the Big Muff, manufacturing them in the USA. We sell several thousand every month.

Getting back to the question, when I went into business the second time around, I became much more conservative. Instead of moving on every single good idea I had, I would wait patiently. As a result, right now, the company is extremely sound financially. We have zero bank debt. We canceled all of our bank lines of credit. We can move on anything we want because of our financial strength. My current design philosophy is I never make a product that takes more than a year to bring it to market. I don’t get involved with designs that go on and on and on. That’s a bad risk. We have a great mix of products and an excellent design team.

I try to keep involved in everything. I still have some accounts I handle myself. I want to make sure I keep my fingers on the pulse. In the old days though, I would decide every single feature of a product. Today, I let engineers come up with creative features.

I still sign all the checks. But more and more, I am trying to delegate some of the things I do. By the time this article is published, I will be 76. I’ve been around (laughs).

The Retailer: How do you control your business in Russia?

The Retailer: How do you control your business in Russia?

Matthews: In 1979, at the trade show, Electro-Harmonix exhibited at in Sokolniki Park in Moscow, and I met Irusha Bitukova. Then, in 1990, we hooked up and visited the Ministry of Electronics together. She is cordial and brilliant. Her father was the co-inventor of the hydrogen bomb in Russia. It was Irusha that found the factory in St. Petersburg where we made the Russian Big Muffs. And it is Irusha that is now director general of our vacuum tube factory and manages all our tube exports all over the world from Russia. She is also a great fisherman and gardener.

The Retailer: A few months ago, you announced you would end your relationship with Amazon. Please provide us with an update on that decision and the changes it has had on your business, your retail network and consumers.

Matthews: Amazon was only five percent of our total business. We are financially strong, so we can afford to take that beating [caused by ending the relationship with Amazon]. The demand for Electro-Harmonix products is not created by Amazon. It’s created by us and our dealers. A lot of consumers look at products in stores and then order on Amazon. Amazon hurts independent music stores, big and small throughout the world. We got a lot of new dealers after our announcement. And for dealers we already have, many of them made bigger orders with us. Since July 1, our business has grown tremendously. Part of it is due to a plethora of new products, and part of it may be support we are getting from stopping sales on Amazon. I don’t know the answer, but we are doing great. Our biggest problem is not building stuff fast enough. Everyone has been working optional overtime. We even were open the Saturday and Sunday [before Thanksgiving] to build products and pack them so that we can fulfill the big growth that we’ve had. There are always problems in business, but right now, we have good problems.

The Retailer: Since this is a NAMM issue, what are your main goals at the show?

The Retailer: Since this is a NAMM issue, what are your main goals at the show?

Matthews: We don’t center everything around The NAMM Show because our daily, ongoing business is big. We go to The NAMM Show to demonstrate our new products. We do pick up some new dealers and see a lot of our existing dealers. The best thing for us at The NAMM Show is our director of marketing, Larry DeMarco, who does a great job organizing and scheduling all the press that comes and does video shoots of our new products. Those video demonstrations at NAMM are a special boon to our business. That is the most important thing for us at NAMM. We don’t view NAMM as a centerpiece of getting big orders. It used to be that way years ago and it used to be that way at the Frankfurt show [Musikmesse]. But now, we do get plenty of orders at The NAMM Show, but the media seeing our stuff and publicizing it throughout the world is the biggest thing for us.

The Retailer: What will we see in the future at Electro-Harmonix?

The Retailer: What will we see in the future at Electro-Harmonix?

Matthews: We are working on a lot of exciting new products. I can’t reveal it, because we have competition throughout the world. When I started the company, there were just two or three companies making sound effects. Now, there are thousands. We are really competing. We can’t try to beat everybody at the same time. In competition, your goal is to win. We want market share. Right now, according to certain reports, we have 10 percent of the world market. There’s room for us to grow in pedals in terms of the existing market. But the music business in general is flat. There are no superstar guitar players everybody wants to be like. No sex symbol idol like when The Beatles came out and The Rolling Stones came out. Young kids now are getting into a lot of things with their cellular phones and computer games. The music business does need a new star to give it stimulation. We as a company have to remain conservative and vigilant. We must be careful with what new products we are coming out with in order to maintain our strong liquidity and strong profits. We don’t want to just survive, but grow.

The Retailer: Anything to add?

Matthews: Rock and roll!